9 Efficient collaboration

Large projects inevitably involve many people. This poses risks but also opportunities for improving computational efficiency and productivity, especially if project collaborators are reading and committing code. This chapter provides guidance on how to minimise the risks and maximise the benefits of collaborative R programming.

Collaborative working has a number of benefits. A team with a diverse skill set is usually stronger than a team with a very narrow focus. It makes sense to specialize: clearly defining roles such as statistician, front-end developer, system administrator and project manager will make your team stronger. Even if you are working alone, dividing the work into discrete branches in this way can be useful, as discussed in Chapter 4.

Collaborative programming provides an opportunity for people to review each other’s code. This can be encouraged by using a uniform style with many comments, as described in Section 9.2. Like using a clear style in human language, following a style guide has the additional advantage of making your code more understandable to others.

When working on complex programming projects with multiple inter-dependencies version control is essential. Even on small projects tracking the progress of your project’s code-base has many advantages and makes collaboration much easier. Fortunately it is now easier than ever before to integrate version control into your project, using RStudio’s interface to the version control software git and online code sharing websites such as GitHub. This is the subject of Section 9.3.

The final section, 9.4, addresses the question of working in a team and performing code reviews.

Prerequisites

This chapter deals with coding standards and techniques. The only packages required for this chapter are lubridate and dplyr. These packages are used to illustrate good practice.

9.1 Top 5 tips for efficient collaboration

- Have a consistent coding style.

- Think carefully about your comments and keep them up to date.

- Use version control whenever possible.

- Use informative commit messages.

- Don’t be afraid to elicit feedback from colleagues.

9.2 Coding style

To be a successful programmer you need to use a consistent programming style. There is no single ‘correct’ style, but using multiple styles in the same project is wrong (Bååth 2012). To some extent good style is subjective and down to personal taste. There are, however, general principles that most programmers agree on, such as:

- Use modular code;

- Comment your code;

- Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY);

- Be concise, clear and consistent.

Good coding style will make you more efficient even if you are the only person who reads it.

When your code is read by multiple readers or you are developing code with co-workers, having a consistent style is even more important. There are a number of R style guides online that are broadly similar, including one by

Google, Hadley Whickham and Richie Cotton.

The style followed in this book is based on a combination of Hadley Wickham’s guide and our own preferences (we follow Yihui Xie in preferring = to <- for assignment, for example).

In-line with the principle of automation (automate any task that can save time by automating), the easiest way to improve your code is to ask your computer to do it, using RStudio.

9.2.1 Reformatting code with RStudio

RStudio can automatically clean up poorly indented and formatted code. To do this, select the lines that need to be formatted (e.g. via Ctrl+A to select the entire script) then automatically indent it with Ctrl+I. The shortcut Ctrl+Shift+A will reformat the code, adding spaces for maximum readability. An example is provided below.

This code chunk works but is not pleasant to read. RStudio automatically indents the code after the if statement as follows.

This is a start, but it’s still not easy to read. This can be fixed in RStudio as illustrated below (these options can be seen in the Code menu, accessed with Alt+C on Windows/Linux computers).

# Automatically reformat the code (Ctrl+Shift+A in RStudio)

if(!exists("x")) {

x = c(3, 5)

y = x[2]

}Note that some aspects of style are subjective: we would not leave a space after the if and ).

9.2.2 File names

File names should use the .R extension and should be lower case (e.g. load.R). Avoid spaces. Use a dash or underscore to separate words.

Section 1.1 of Writing R Extensions provides more detailed guidance on file names, such as avoiding non-English alphabetic characters since they cannot be guaranteed to work across locales. While the guidelines are strict, the guidance aids in making your scripts more portable.

9.2.3 Loading packages

Library function calls should be at the top of your script. When loading an essential package, use library instead of require since a missing package will then raise an error. If a package isn’t essential, use require and appropriately capture the warning raised. Package names should be surrounded with speech marks.

Avoid listing every package you may need, instead just include the packages you actually use. If you find that you are loading many packages, consider putting all packages in a file called packages.R and using source appropriately.

9.2.4 Commenting

Comments can greatly improve the efficiency of collaborative projects by helping everyone to understand what each line of code is doing. However comments should be used carefully: plastering your script with comments does not necessarily make it more efficient, and too many comments can be inefficient. Updating heavily commented code can be a pain, for example: not only will you have to change all the R code, you’ll also have to rewrite or delete all the comments!

Ensure that your comments are meaningful. Avoid using verbose English to explain standard R code. The comment below, for example, adds no useful information because it is obvious by reading the code that x is being set to 1:

Instead, comments should provide context. Imagine x was being used as a counter (in which case it should probably have a more meaningful name, like counter, but we’ll continue to use x for illustrative purposes). In that case the comment could explain your intention for its future use:

The example above illustrates that comments are more useful if they provide context and explain the programmer’s intention (McConnell 2004). Each comment line should begin with a single hash (#), followed by a space. Comments can be toggled (turned on and off) in this way with Ctl+Shift+C in RStudio. The double hash (##) can be reserved for R output. If you follow your comment with four dashes (# ----) RStudio will enable code folding until the next instance of this.

9.2.5 Object names

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in a rather scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean - neither more nor less.”

- Lewis Carroll - Through the Looking Glass, Chapter 6.

It is important for objects and functions to be named consistently and sensibly. To take a silly example, imagine if all objects in your projects were called x, xx, xxx etc. The code would run fine. However, it would be hard for other people, and a future you, to figure out what was going on, especially when you got to the object xxxxxxxxxx!

For this reason, giving a clear and consistent name to your objects, especially if they are going to be used many times in your script, can boost project efficiency (if an object is only used once, its name is less important, a case where x could be acceptable). Following discussion in (Bååth 2012) and elsewhere, suggest an underscore_separated style for function and object names23. Unless you are creating an S3 object, avoid using a . in the name (this will help avoid confusing Python programmers!). Names should be concise yet meaningful.

In functions the required arguments should always be first, followed by optional arguments. The special ... argument should be last. If your argument has a boolean value, use TRUE/FALSE instead of T/F for clarity.

It’s tempting to use T/F as shortcuts. But it is easy to accidentally redefine these variables, e.g. F = 10. R raises an error if you try to redefine TRUE/FALSE.

While it’s possible to write arguments that depend on other arguments, try to avoid using this idiom

as it makes understanding the default behaviour harder to understand. Typically it’s easier to set an argument to have a default value of NULL and check its value using is.null than by using missing.

Where possible, avoid using names of existing functions.

9.2.6 Example package

The lubridate package is a good example of a package that has a consistent naming system, to make it easy for users to guess its features and behaviour. Dates are encoded in a variety of ways, but the lubridate package has a neat set of functions consisting of the three letters, year, month and day. For example,

9.2.7 Assignment

The two most common ways of assigning objects to values in R is with <- and =. In most (but not all) contexts, they can be used interchangeably. Regardless of which operator you prefer, consistency is key, particularly when working in a group. In this book we use the = operator for assignment, as it’s faster to type and more consistent with other languages.

The one place where a difference occurs is during function calls. Consider the following piece of code used for timing random number generation

The first lines will run correctly and create a variable called expr1. The second line will raise an error. When we use = in a function call, it changes from an assignment operator to an argument passing operator. For further information about assignment, see ?assignOps.

9.2.8 Spacing

Consistent spacing is an easy way of making your code more readable. Even a simple command such as x = x + 1 takes a bit more time to understand when the spacing is removed, i.e. x=x+1. You should add a space around the operators +, -, \ and *. Include a space around the assignment operators, <- and =. Additionally, add a space around any comparison operators such as == and <. The latter rule helps avoid bugs

The exceptions to the space rule are :, :: and :::, as well as $ and @ symbols for selecting sub-parts of objects. As with English, add a space after a comma, e.g.

9.2.9 Indentation

Use two spaces to indent code. Never mix tabs and spaces. RStudio can automatically convert the tab character to spaces (see Tools -> Global options -> Code).

9.2.10 Curly braces

Consider the following code:

Typing this straight into R will result in an error. An opening curly brace, { should not go on its own line and should always be followed by a line break. A closing curly brace should always go on its own line (unless it’s followed by an else, in which case the else should go on its own line). The code inside curly braces should be indented (and RStudio will enforce this rule), as shown below.

Exercises

Look at the difference between your style and RStudio’s based on a representative R script that you have written (see Section 9.2). What are the similarities? What are the differences? Are you consistent? Write these down and think about how you can use the results to improve your coding style.

9.3 Version control

When a project gets large, complicated or mission-critical it is important to keep track of how it evolves. In the same way that Dropbox saves a ‘backup’ of your files, version control systems keep a backup of your code. The only difference is that version control systems back-up your code forever.

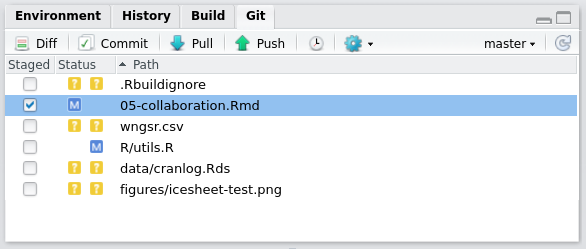

The version control system we recommend is Git, a command-line application created by Linus Torvalds, who also invented Linux.24 The easiest way to integrate your R projects with Git, if you’re not accustomed to using a shell (e.g. the Unix command line), is with RStudio’s Git tab, in the top right-hand window (see figure 9.1). This shows a number of files have been modified (as illustrated with the blue M symbol) and that some are new (as illustrated with the yellow ? symbol). Checking the tick-box will enable these files to be committed.

9.3.1 Commits

Commits are the basic units of version control. Keep your commits ‘atomic’: each one should only do one thing. Document your work with clear and concise commit messages, use the present tense, e.g.: ‘Add analysis functions’.

Committing code only updates the files on your ‘local’ branch. To update the files stored on a remote server (e.g. on GitHub), you must ‘push’ the commit. This can be done using git push from a shell or using the green up arrow in RStudio, illustrated in figure 9.1. The blue down arrow will ‘pull’ the latest version of the repository from the remote.25

Figure 9.1: The Git tab in RStudio

9.3.2 Git integration in RStudio

How can you enable this functionality on your installation of RStudio? RStudio can be a GUI Git only if Git has been installed and RStudio can find it. You need a working installation of Git (e.g. installed through apt-get install git Ubuntu/Debian or via GitHub Desktop for Mac and Windows). RStudio can be linked to your Git installation via Tools > Global Options, in the Git/SVN tab. This tab also provides a link to a help page on RStudio/Git.

Once Git has been linked to your RStudio installation, it can be used to track changes in a new project by selecting Create a git repository when creating a new project. The tab illustrated in figure 9.1 will appear, allowing functionality for interacting with Git via RStudio.

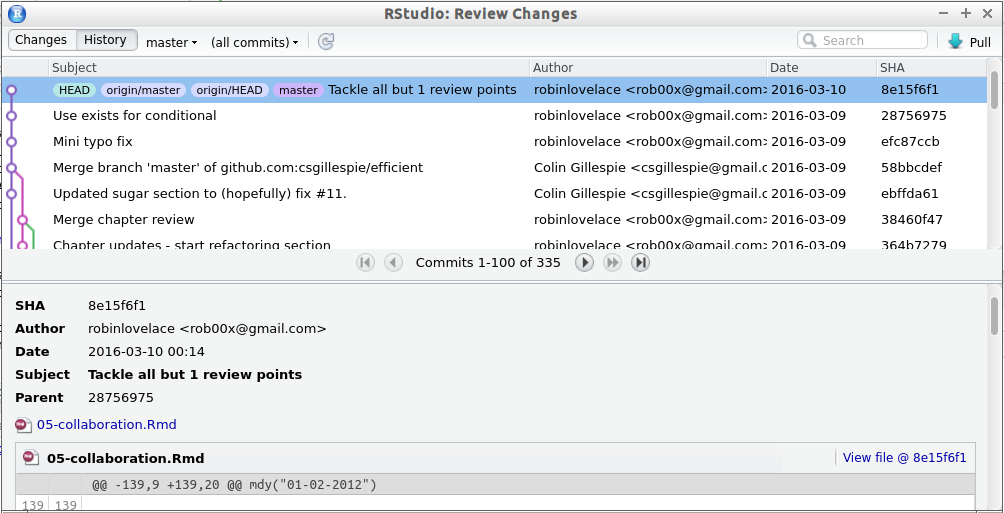

RStudio provides a useful GUI for navigating past commits. This allows you to see the entire history of your project. To navigate and view the details of past commits click on the Diff button in the Git pane, as illustrated in figure 9.2.

Figure 9.2: The Git history navigation interface

9.3.3 GitHub

GitHub is an online platform that makes sharing your work and collaborative code easy. There are alternatives such as GitLab. The focus here is on GitHub as it’s by far the most popular among R developers. Also, through the command devtools::install_github(), preview versions of a package can be installed and updated in an instant. This makes ‘GitHub packages’ a great way to access the latest functionality. And GitHub makes it easy to get your work ‘out there’ to the world for efficiently collaborating with others, without the restraints placed on CRAN packages.

To install the GitHub version of the benchmarkme package, for example one would enter

Note that csgillespie is the GitHub user and benchmarkme is the package name. Replacing csgillespie with robinlovelace in the above code would install Robin’s version of the package. This is useful for fast collaboration with many people, but you must remember that GitHub packages will not update automatically with the command update.packages (see 2.3.5).

Warning: although GitHub is fantastic for collaboration, it can end up creating more problems than it solves if your collaborators are not git-literate. In one project, Robin eventually abandoned using GitHub to collaborate after his collaborator found it impossible to work with. More time was being spent debugging git/GitHub than actually working. Our advice therefore is to never impose git and always ensure that other lines of communication (e.g. phone calls, emails) are open as different people prefer different ways of communicating.

9.3.4 Branches, forks, pulls and clones

Git is a large program which takes a long time to learn in depth. However, getting to grips with the basics of some of its more advanced functions can make you a more efficient collaborator. Using and merging branches, for example, allows you to test new features in a self-contained environment before it is used in production (e.g. when shifting to an updated version of a package which is not backwards compatible). Instead of bogging you down with a comprehensive discussion of what is possible, this section cuts to the most important features for collaboration: branches, forks, fetches and clones. For a more detailed description of Git’s powerful functionality, we recommend Jenny Byran’s book, “Happy Git and GitHub for the useR”.

Branches are distinct versions of your repository. Git allows you to jump seamlessly between different versions of your entire project. To create a new branch called test, you need to enter the shell and use the Git command line:

This is the equivalent of entering two commands: git branch test to create the branch and then git checkout test to checkout that branch. Checkout means switch into that branch. Any changes will not affect your previous branch. In RStudio you can jump quickly between branches using the drop down menu in the top right of the Git pane. This is illustrated in figure 9.1: see the master text followed by a down arrow. Clicking on this will allow you to select other branches.

Forks are like branches but they exist on other people’s computers. You can fork a repository on GitHub easily, as described on the site’s help pages. If you want an exact copy of this repository (including the commit history) you can clone this fork to your computer using the command git clone or by using a Git GUI such as GitHub Desktop. This is preferable from a collaboration perspective compared to cloning the repository directly, because any changes can be pushed back online easily if you are working from your own fork. You cannot push to forks that you have not created. If you want your work to be incorporated into the original fork you can use a pull request. Note: if you don’t need the project’s entire commit history, you can simply download a zip file containing the latest version of the repository from GitHub (see at the top right of any GitHub repository).

A pull request (PR) is a mechanism on GitHub by which your code can be added to an existing project. One of the most useful features of a PR from a collaboration perspective is that it provides an opportunity for others to comment on your code, line by line, before it gets merged. This is all done online on GitHub, as discussed in GitHub’s online help. Following feedback, you may want to refactor code, written by you or others.

9.4 Code review

What is a code review?26 Simply when we have finished working on a piece of code, a colleague reviews our work and considers questions such as

- Is the code correct and properly documented?

- Could the code be improved?

- Does the code conform to existing style guidelines?

- Are there any automated tests? If so, are they sufficient?

A good code review shares knowledge and best practice.

A lightweight code review can take a variety of forms. For example, it could be as simple as emailing round some code for comments, or “over the shoulder”, where someone literally looks over your shoulder while coding. More formal techniques include paired programming where two developers work side by side on the same project.

Regardless of the review method being employed, there a number of points to remember. First, as with all forms of feedback, be constructive. Rather than pointing out flaws, give suggested improvements. Closely related is give praise when appropriate. Second, if you are reviewing a piece of code set a time frame or the number of lines of code you will review. For example, you will spend one hour reviewing a piece of code, or a maximum of 400 lines. Third, a code review should be performed before the code is merged into a larger code base; fix mistakes as soon as possible.

Many R users don’t work in team or group; instead they work by themselves. Practically, there isn’t anyone nearby to review their code. However there is still the option of an unoffical code review. For example, if you have hosted code on an online repository such as GitHub, users will naturally give feedback on our code (especially if you make it clear that you welcome feedback). Another good place is StackOverflow (covered in detail in chapter 10). This site allows you to post answers to other users questions. When you post an answer, if your code is unclear, this will be flagged in comments below your answer.

References

Bååth, Rasmus. 2012. “The State of Naming Conventions in R.” The R Journal 4 (2): 74–75. https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2012-2/RJournal_2012-2_Baaaath.pdf.

McConnell, Steve. 2004. Code Complete. Pearson Education.

One notable exception are packages in Bioconductor, where variable names are

camelCase. In this case, you should match the existing style.↩︎We recommend ‘10 Years of Git: An Interview with Git Creator Linus Torvalds’ from Linux.com for more information on this topic.↩︎

For a more detailed account of this process, see GitHub’s help pages.↩︎

This section is being written with small teams in mind. Larger teams should consult a more detailed text on code review.↩︎